Bedding Down at East Mains

Stewartfield No.4 pit, and its visitors.

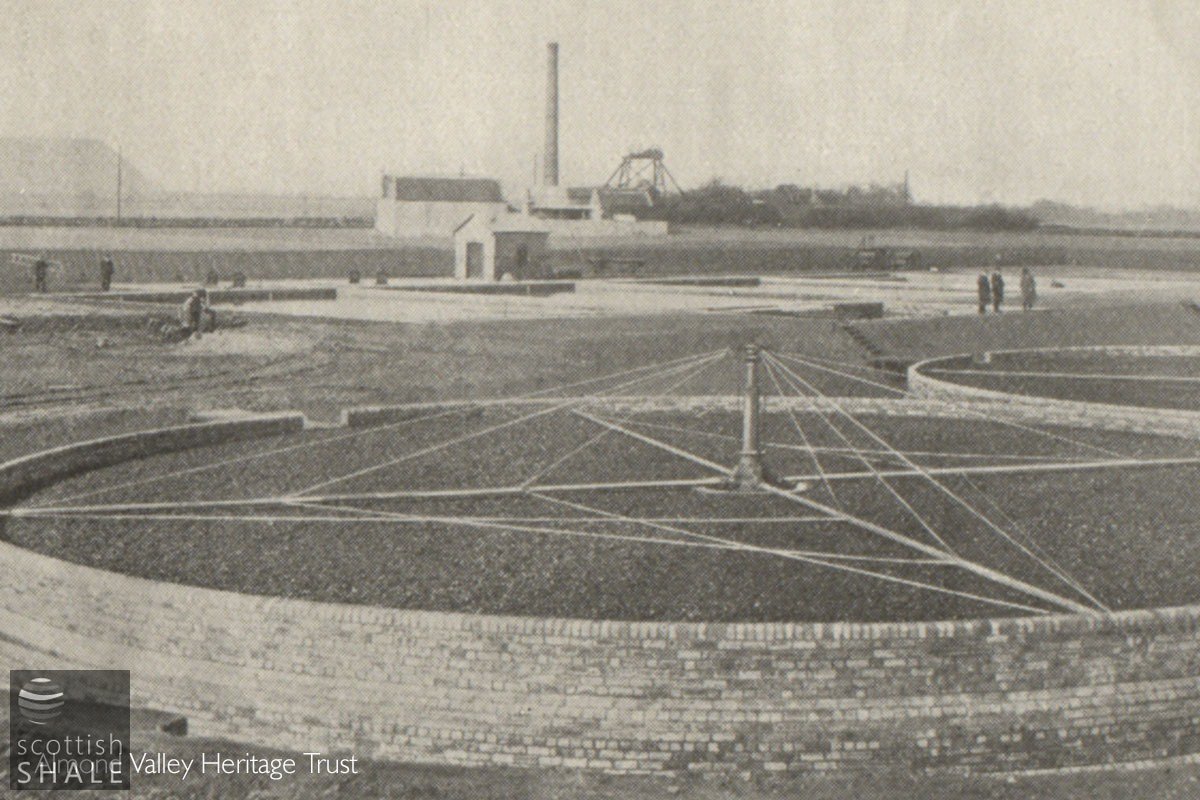

Broxburn fine new sewage works at Burnside, pictured in about 1914, and looking north towards the chimney stalk and headgear of "Law's pit".

Setting up home at Law's pit, Broxburn.

The snapshot has "law's pit" scribbled on the back suggesting some local knowledge.

Tending to your budgie, with shale bings behind.

Taking the weight off your feet - with East Mains farm in the background.

F19020, first published 10th May 2019

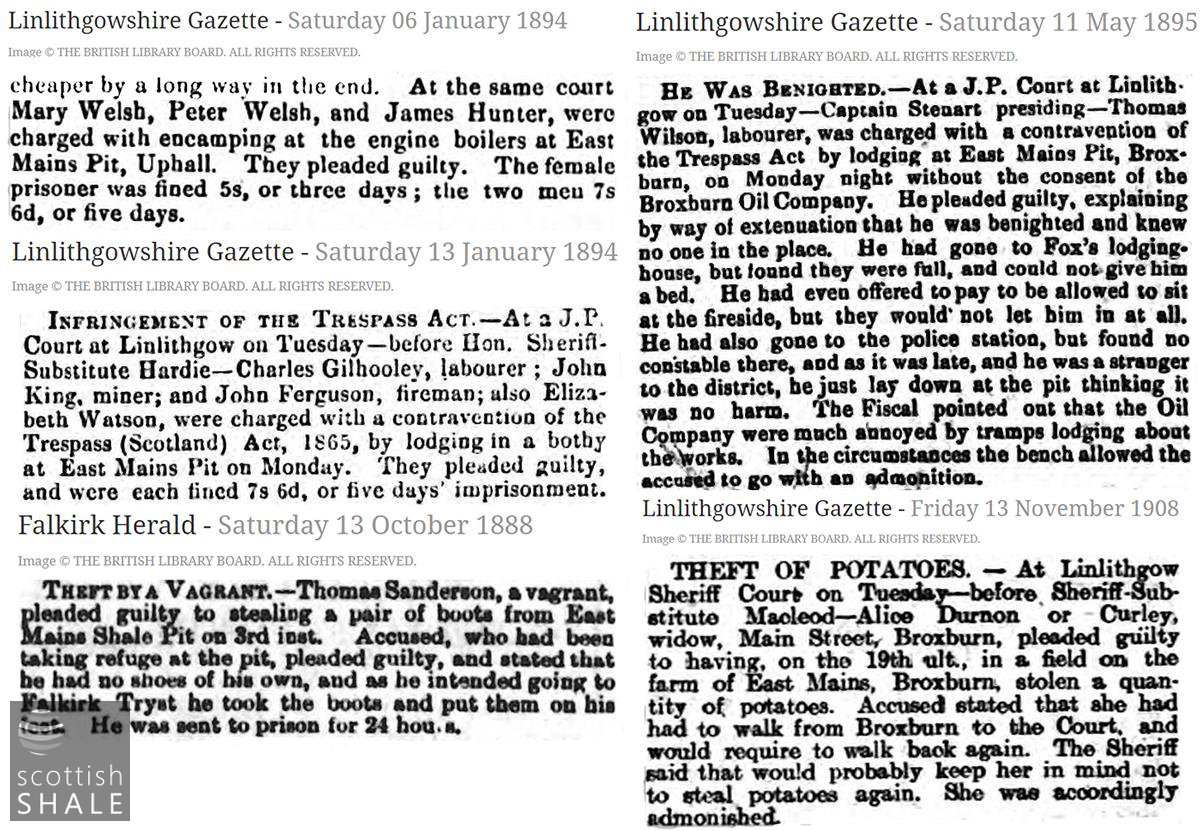

On a cold winter’s night, the big smoking lum of Law’s pit must have been a welcome sight to the gentlemen (and occasional lady) of the road as they tramped their way between Scotland’s industrial centres. For a period the boiler-house and bothies of the shale pit offered the prospect of a little shelter from the wind and rain, and somewhere warm to lay your head for the night.

Law’s pit – officially “Stewartfield No.4” or “East Mains” was sunk by the Broxburn Oil Company, probably at some time during the 1880’s. It is was sited immediately beside the main Edinburgh to Glasgow road, about half a mile east of Broxburn, within the lands of James Law’s East Mains farm. The vertical shaft dropped to the Broxburn shale 84 fathoms (about 150 metres) beneath, and was mainly used to pump away water from the lowest point of a network of workings that plummet into the ground beneath the old town of Broxburn. The shale worked in the area was hauled through steeply inclined workings to reach the surface at Stewartfield No.2 mine, just south of the Union canal.

Set out in the countryside, Law’s pit would have been a quiet corner, with little more than an engine-man and fireman on shift to keep the steam-powered pumps running day and night. Out-of-sight of management but right beside the main road, it became accepted that overnight lodging might be available in the warmth of the boiler-room in return for a few hours work stoking boilers or shoveling ashes.

As knowledge spread, the number of travelers and itinerant workers seeking hospitality became a nuisance. Tramps were blamed when potatoes and turnips disappeared from surrounding fields, careless smoking set fire to straw sheds and haystacks, and locks were forced on secure buildings. Sometimes oil company workers found themselves outnumbered and overpowered, unable to prevent entry or exercise control over their “guests”.

The oil company became aware of the problem, and police action was taken. In March 1893, one police raid netted a haul of 13 “tramps”, the youngest 19, the oldest 80. In court it was established that none of the shabby crew “belonged to Broxburn”; all were tramps, part of a huge itinerant army who roamed the country in search of work. The group were threatened with prison should they ever again “interfere with an engine-man in the exercise of his duty”. It was reported that on release “the heterogeneous squad of the great unwashed were observed to break off in all directions in quest of pastures new”.

The Stewartfield pits closed in 1914, and the pumps of Law’s pit probably fell silent at that time. The tall chimney stalk, which was a prominent local landmark, was felled soon after. The pithead rubbish heaps of ashes, shale and fragments of coal were picked over during time of strike, and in 1921 a fire broke out that attracted a large crowd of spectators. “A watchman was posted to prevent anyone from the young fraternity getting too venturesome”

Our three snapshots of Law’s pit seem to date from around 1930. A well-dressed couple with a smart Glasgow-registered motor car seem quite at home among the long summer grass of the overgrown mine site. The heap of ash and cinder provides some shelter, there’s a glimpse of East Mains farm, and the majestic bulk of the Broxburn bings rise in the background.

The tent, the budgies, and a covered trailer carrying home comforts, suggest an overnight stay or a camping holiday rather than just a picnic in the countryside. But we’ll probably never know who these good folk were and why they chose to set up a temporary home at the site of the old pumping station.

In the mid 1960’s the mine site, the farmhouse and the open fields disappeared beneath a new East Mains industrial estate.