Fragrant Winchburgh

The Triumph of Decent Toilets

F20019, first published 10th May 2020

A clean and private place to perform your bodily functions was once only a distant dream for many working folk. In worker's housing built in the early years of the shale oil industry, the only toilets available were dry pail closets or ”shunkies” - little brick outhouses at the rear of the homes shared with many of your neighbours. The company employed a "scavenger" who once or twice a week would scoop up a fragrant mixture of human waste and ashes, then cart this away to be spread on local fields. Filthy conditions, lack of privacy and fear of disease meant that many resorted to buckets, chamber pots, and journeys to the woods and fields under the cover of darkness. The introduction of the

water closet brought a new age of modesty and hygiene, and at the start of the 20th century the Winchburgh area offered examples of some of the best toilet provision in the shale districts; and some of the worst.

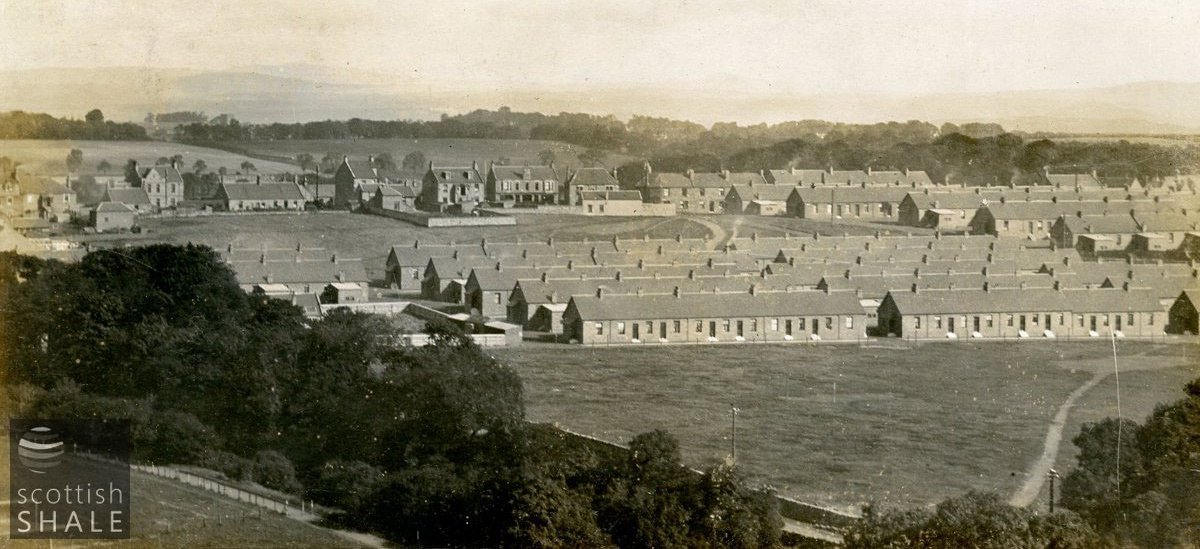

Niddry rows lay half a mile south of Winchburgh, close to the smoke and grime of Hopetoun oil works, and in the shadow of its ever-growing bings of shale waste. It was home to nearly 700 people, living in houses with two, or just a single room. Some dated back to the opening of the oilworks in about 1872. It was said that poor housing bred bad behaviour, and it seems that residents of the rows spent a disproportional amount of time in court, answering charges of assault and disorderly conduct. There were also many appearances relating to theft of potatoes, turnips, chickens and other produce from local farms and gardens.

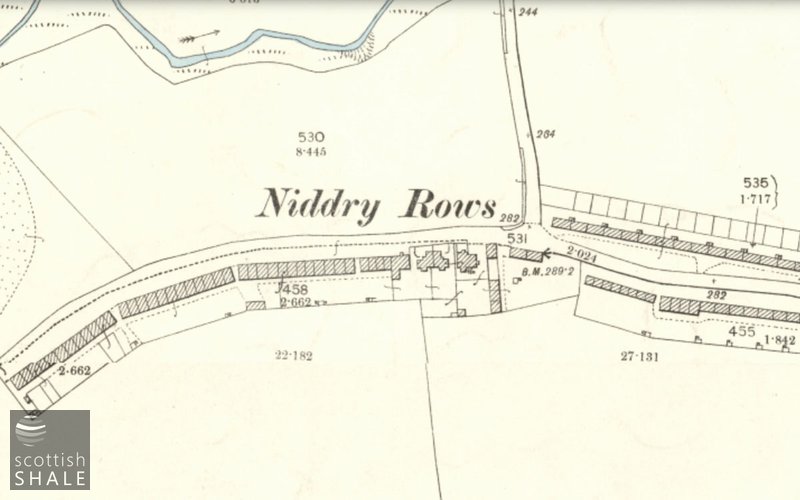

The Council's Sanitary Inspector often reported on problems at Niddry Rows. There were instances of overcrowding, outbreaks of infection diseases, and reports of privvies and ashpits in a “filthy and delapidated condition”. The 1896 ordnance survey map suggests that there were fewer than 20 privvy buildings to serve the entire village. Following action by the sanitary inspector, Youngs's oil company were required to construct 40 new privvies in 1906, and make many other improvements to drainage. Each pail closet continued to be shared by two households until 1935, when many of the rows were demolished following a slum clearance order.

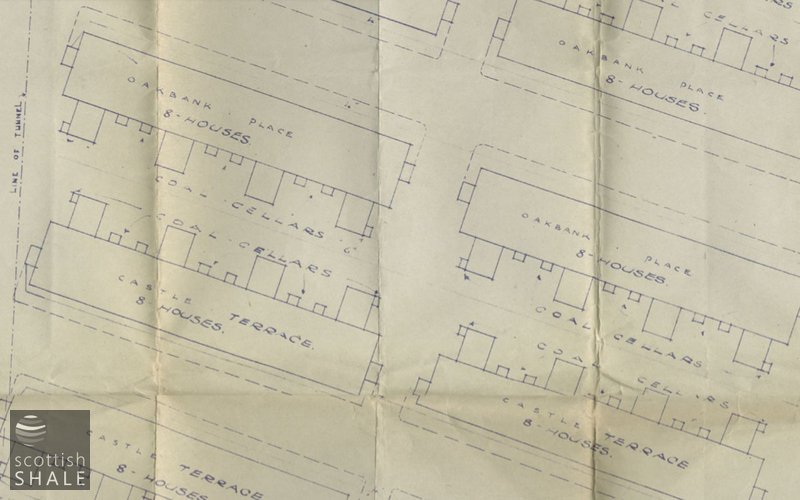

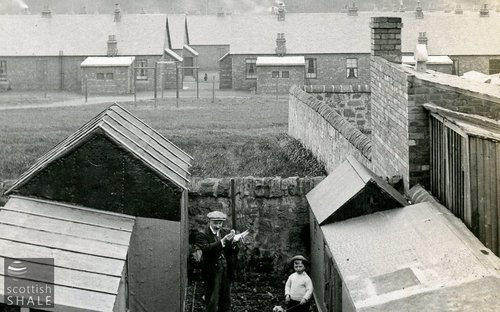

In constrast, the housing constructed in Winchburgh by the Oakbank Oil Company were among the first in the shale districts to be fitted with indoor flushing toilets. The company's new mines in Duddingston, and their new Niddry Castle oil works in Winchburgh, introduced many innovations, and similar progressive thinking was applied to the housing of their workforce. In 1902 construction began on 200 new houses. While simple and lacking in decoration, these new homes built in Winchburgh provided two large

rooms plus a scullery and wc projecting from the rear of each row. The sanitary inspector was involved in the design of the housing and later reported “I am glad to see each house fitted with boiler and large sink, water closet, a galvanised dust-bin and coal-cellar. When completed, these houses will be the most modern miner's dwellings in the District. It is said …......that the moral and social conditions of men is governed principally be their environment. If this is so, we will naturally expect a high standard of morality amongst the miners in Winchburgh, for their dwellings leave little or nothing to be desired.” His expectations seem to have been well-founded as the Winchburgh rows continue to provide solid and desirable homes, and retain a great sense of community.

While the new oilworks and housing in Winchburgh were under construction, the struggling Linlithgow Oil Company was finally declared bankrupt. Many of the skilled oil workers previously employed at their Champfleurie oil works were able to find new jobs at Niddry Castle. Many were particularly pleased to move to Winchburgh from their old homes in Bridgend and Kingscavil as the liquidator of the collapsed company had failed to pay the wages of the scavenger. As a consequence it was reported that “the privies are full and overflowing, and complaints are many.”

In 1907, further extension of the Duddingston mines required the construction of 50 more new houses in Winchburgh. The original building contractors, Topping & Co., and their army of itinerant workers, were brought back to carry out the work. The sanitary inspector has left an unusually detailed account of the primitive living conditions of these temporary workers, and their basic (and doubtless pungent), toilet arrangements:

“The hut is a wooden erection, covered with felt, and contains 25 double beds. It was in use for several weeks without any sanitary conveniences whatever having been provided for the use its occupants....... action was taken against the proprietor,.......... Water has been introduced, and attempt made to provide a closet. The closet consists of a trench about 6 feet deep and 2 feet wide dug in the ground and surrounded coarse boarding. When trench is full, it is covered over, and a new one provided a distance from it.”

Above top left: Re-construction work in progress at Hopetoun oil works in 1908. The Niddry Rows can be glimpsed on the skyline. Above left: Doos and rows, the projections from the rear of the Winchburgh rows, containing scullery and w.c., can be clearly seen. Above right: All the comforts of home. An early WC in oil company housing in Seafield.