Fence Houses Oil Works

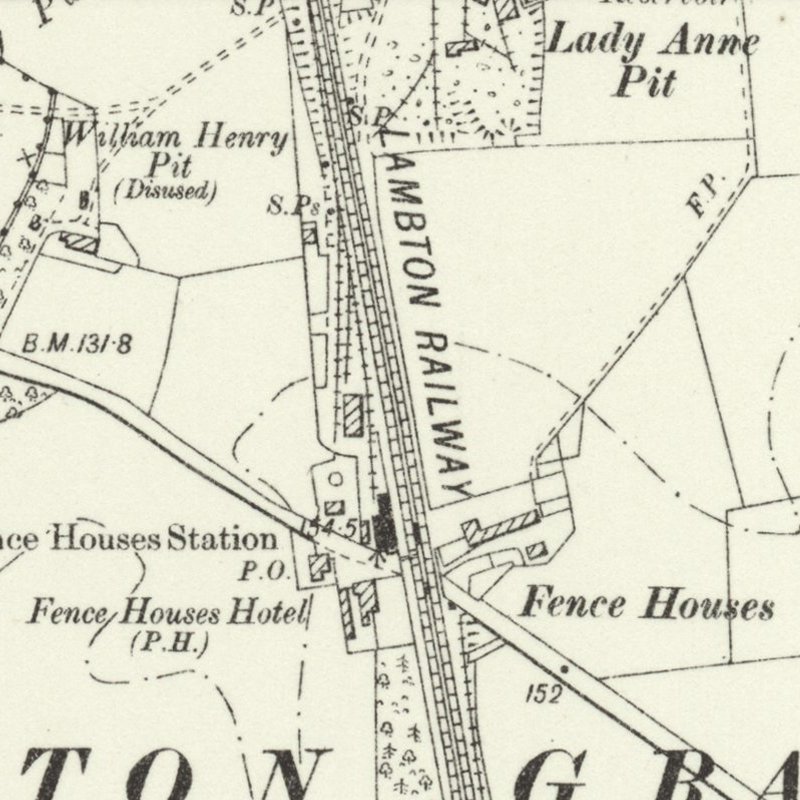

"The Engineer" of June 1866 included drawings of retorts manufactured by the Glasgow firm of George Bennie & Co which were supplied to the "Lambton Mineral Oil Works, Fence-House near Durham." The accompanying text (see below under Resources) stated:

"... the engravings show a small section of the works to be established by Lord Durham, which will, when complete, cover several acres, and will possibly constitute the most extensive establishment of the kind in the kingdom. "

The report stated that the retorts were then complete and it was planned to construct stills for refining the crude oil.

It seems likely that this account described the oil works of Ferdinand Jossa, who presumably leased the site from The Earl of Durham. The 1861 census records that Ferdinand Jossa, age 47, a manufacturing chemist born in Spain, was boarding at 13 Ann St. South Bishopwearmouth. He was married at Easington in 1862.

Jossa had patented a process for "consumption of smoke and saving of fuel" in boilers, and advertised his invention in the Newcastle Courant and other papers during 1857. These gave his address as Saint Helen's Colliery near Bishop Auckland. In 1860 he established a chemical manufacturing business at Murton Colliery, near Seaham using capital "brought from the continent". This enterprise operated at a loss and was sold off in 1865. He then began construction of the Fence Houses Oil Works, which sought to produce oil using waste shale from local local coal pits. Little expense seems to have seems to have been spared in equipping the works, but when the price of oil collapsed, the business quickly became unviable. Jossa was declared bankrupt in about 1868.

The 1880 US census records Ferdinand Jossa, manufacturing chemist, living in New York City.

Retorts for Fencehouses Oil Works

Coal Oil

Within the last few years a manufacture of considerable importance has sprung up in Great Britain, of which very little is known save by those closely interested in its success, or engaged in carrying it on. It is pretty generally understood that by treating any bituminous coal in the proper way, certain highly valuable products can be obtained in lieu of gas. These may be classed under three heads, volatile combustible fluids, a heavy oil, and the peculiar substance known as paraffin, now largely employed in the manufacture of candles. It was long held, however, that these products could only be extracted with profit from highly bituminous shale, such as the celebrated Torbane-hill mineral, and few attempts were made in this country to obtain them from ordinary coal. It is possible that so little was known about the coal oils that no appreciable demand for them existed, but the introduction of petroleum and mineral lubricating oils from America quickly established a market which it became worth while to supply, and such improvements have been introduced from time to time in the distilling and purifying apparatus that, as we have said, the conversion of bituminous coal, has become a branch of manufacturing industry, gaining in importance and extent each day.

The discovery of the fact that oil could be obtained by destructive distillation appears to have been first made by Clayton in 1739. In the year 1805 Mr. Northern called attention to coal gas, and, as a matter of course, in making it obtained a considerable quantity of crude oil. Little importance was attached to the circumstance, and the matter was not pursued until the middle of the present century.. The only result, indeed, which appears to have followed from Northern's labours as far as concerns coal oil at all events, was the manufacture of tar in considerable quantities for the use of our navy, to replace Archangel tar, which had become excessively scarce and dear. In 1850 Young took out his celebrated patent, and from the moment he undertook the manufacture of coal oil on a commercial scale it may be regarded as having been established on a permanent basis in this country. At a comparatively early stage Young obtained from l00 parts of cannel coal 40 of oil and 10 of paraffin, while the residual coke was by no means valueless. This was sufficient to prove that the process could be made remunerative, and very considerable sums are now embarked in the business in various places in Great Britain.

It would be impossible within the limits of an article like this to go deeply into the chemistry of the subject, but we can explain in a few words the rationale of the process. When coal is heated in a retort, under such conditions that it can only be exposed to the action of oxygen which it contains itself, the following changes take place:-While the heat is moderate aqueous vapour, organic acids, ammonia, and some combustible fluids soluble in water are given off. As the temperature rises, carbonic acid, carbonic oxide, and a number of oleaginous products not soluble in water are surrendered. When the temperature reaches a red heat the products of the distillation become almost wholly gaseous, the oils being converted into permanent gases before leaving the retort. The maker of gas therefore, takes especially care that the temperature of his retorts shall not fall much below 1,200 deg. or 1,400 deg., while the maker of coal oil is yet more careful that the temperature shall not exceed 700 deg. The production of gas commences, in short, at a heat where that of oil ceases. The oil as it comes over is a compound of many substances- so many that a list of them would surprise our non-chemical readers by its length. It will suffice to say, however, that to the manufacturer they present themselves in the form of a thick, dark-coloured, tarry fluid, of little or no value until it has undergone a process of purification. This is accomplished by digesting the fluid with various substances, such as sulphate of iron, which removes the ammonia, sulphuric acid, &c., and subsequently re-distilling the oil, generally by the aid of super-heated steam. Further manipulations leave the manufacturer in possession of two oils, one light and one heavy, and the solid known as paraffin; the proportion which the substances bear to each other varying with the quality of the coal, the mode of distillation, and several other conditions. It will be seen from the foregoing that the success of the manufacturer depends almost wholly on the care with which certain conditions are observed in the very first stages of the process. A writer of some eminence, in speaking on this point, says, "No question is so important to the manufacturer of photogenic oils as that which presents itself in the construction and arrangement of the retorts; all other questions are subordinate to this. The mode of purification, and even the selection of the coal, are of less importance than obtaining from a given weight of material, all of the heavy and volatile oil which can be got. The truths involved in this proposition have long been recognised, and many different systems of distillation have been proposed; but it does not appear that complex arrangements have commanded success, and it is certain that in this country the manufacture of coal oil apparatus is confined to a very few firms indeed. We shall not be far wrong if we estimate the good qualities or the arrangements which they adopt by their popularity.

On another page we illustrate a set of retorts now being erected for the Earl of Durham, by Messrs. George Bennie and Co.- who have courteously placed their working drawings at our disposal- which embodies all the latest improvements in this branch of engineering effected by a firm more largely engaged than any other in the trade. The works of the firm, indeed, at Kinning Park, near Glasgow, form a very extensive establishment, and one well worthy of note, even in a city celebrated for the magnitude of its foundry operations. Our engraving illustrates but a small section of the works to be established by Lord Durham, which will, when complete, cover several acres, and will possibly constitute the most extensive establishment of the kind in the kingdom. The apparatus at present consists of twenty retorts, constructed on two different systems with a view to determine which is the better of the two; the stills for the purification of the crude oil have not yet been erected. In order to bring the illustration within the limits of our pages, we have omitted one block of vertical retorts, but this differs in no respect from that shown. Twelve of the retorts (shown in Figs. 1, 2, and 3) are horizontal, and eight (Figs. 4 and 5) are vertical-on Young's principle. The charging of the first is performed in the ordinary way from the front through a luted door, the coke being withdrawn as soon as the charge is exhausted. The vertical retorts are, on the contrary, fed periodically with small charges introduced at the top, while the coke is withdrawn from the bottom. The construction of the horizontal retorts is so simple that we fancy any minute description is not required. The vertical retorts are simply cast iron tubes, the lower ends dipping into a vessel containing water which acts as a lute, while the upper ends are fitted with a charging apparatus consisting of a hopper or funnel-head closed by a cone drawn up from below by the balance-weights and arc-head shown. The coal, broken small, is delivered into the hopper head from a barrow, and from time to time the balance-weight is raised by the man in charge. The conical lid, shown by dotted lines in Fig. 5, descends and distributes the broken coal towards the sides of the retort, on a principle which has been adopted with some success in feeding blast furnaces. The merits of the two systems may be thus be expressed. It is now held as an established fact that horizontal retorts produce the lightest crude oil. By manufacturers who sell their oil in the crude state to the refiner this must be regarded as an advantage paramount to all other considerations, if we are to judge by the prices which have been obtained for heavy and light crude oils during the past year. If, however, the manufacturer refines his own oil, or even distils it once only, the case assumes a totally different aspect. He then separates the heavy from the light oil, sells them for different uses, and occasionally obtains a higher price for heavy refined oil for lubricating purposes than he can obtain for light oil intended for burning; and from this it may be assumed that if the number of refiners in this country was to increase relatively to the number of works which have retorts only, the practical bearing of the question regarding the merits of horizontal versus vertical retorts would undergo a considerable change. On the side of the vertical retorts, it may be said that they produce a larger quantity of oil from a given weight of coal; that they are more economically worked; and that they are more durable than their rivals. As regards this last fact, indeed, Mr. Bennie informs us that be has found the vertical retort last fully ten times as long as the horizontal. The statement is perfectly consistent with the conditions under the retorts are worked. At the time of drawing the charge from the horizontal retort, the internal surface is exposed to a sudden chill from the atmosphere, and not unfrequently the retort is re-charged while at a high temperature with cold wet shale. We all know pretty well what results when cold water is thrown on red-hot cast iron. Now in working the vertical retort the interior is never exposed to chills in the same way. It is never emptied, and the charge first comes in contact with the metal at the top where it is comparatively cold, and descends gradually to the hotter region below. Even though it were exposed to the same chills it is probable that it would stand better owing to its vertical position. When a horizontal retort is overheated it bends downward in the centre and then gives way, because the shape assumed does not permit equable contraction in cooling. It is clear that the vertical retort is not exposed to a similar contingency. The vertical retort works up about 15 cwt. of shale per day of twenty-four hours; the horizontal from 20 cwt. to 30 cwt., according to the hardness of the material. In some cases twelve hours is sufficient to extract all the oil; in others a period of twenty-four hours is required to effect the same object.

Mr. Bennie uses only cast iron for his stills, and he informs us that he has adopted this practice as a result of several years' careful observation of the working of stills of both cast and wrought iron. Cast iron first used did not stand, and wrought iron was adopted, but the change was of little service. The former cracked, but the latter leaked at the joints more oil than would have purchased the stills many times over, and this notwithstanding constant caulking. Yet an important problem remained for solution. Could a cast iron still be procured which would stand the work? To the solution of this problem Mr. Bennie devoted much attention, and by the use of a peculiar mixture of cast iron, and by casting the stills bottom downward so as to impart the greatest density to that part most exposed to heat, he has succeeded in completely overcoming a very serious difficulty, and he now finds himself fully employed in carrying out orders for stills of the very material which bid fair to be rejected for ever a few years since. The construction of the stills is exceedingly simple. The oil is charged through a suitable apparatus, and the products of distillation are condensed sometimes in a long pipe, which is coiled within a water cistern, at others led along the face of a long wall two or three times to obtain sufficient surface. Superheated steam is turned into the oil and plays an important part in the distillation. The superheating apparatus invented by Mr. Bennie is exceedingly ingenious, and has, we understand, given so much satisfaction that we commend it to the notice of marine engineers. In the roof of the furnace is fitted a block of cast iron, which is of course maintained at a red heat or nearly so. The interior of the block is traversed by a serpentine wrought iron pipe, through which the steam passes. The pipe is effectively protected by the cast iron, and the steam is delivered at a very high temperature to the oil. Mr. Bennie does not confine himself to the arrangement of retorts we have illustrated. We have engravings in hand of a somewhat different system, now being erected in Yorkshire, which will clearly illustrate the construction of the refining stills. When placing them before our readers, we shall say something of the Kinning Park Foundry, the only establishment in Great Britain, we believe, exclusively devoted to the production of coal-oil apparatus.

Engineer, 22nd June 1866

THE MANUFACTURE OF PARAFFIN OIL, &c.

We understand that works are to be established at Fence Houses, in the county of Durham, for the manufacture of paraffin, lubricating oil, and grease from a description of material which the coal mines of that district abundantly supply. It is a fact – and yet strange to say, we seem hitherto not to have been aware of it, or alive to it—that we need be indebted to America, and other countries, quantity of the oil so extensively needed domestic, mercantile, and manufacturing establishments, when we have before us and about us a mineral substance possessing all the essential elements and capable of being easily converted to a liquid or semi-liquid character, such as we have already enumerated.

A Mr Ferdinand Jossa, of Sunderland, who was up to within a recent period, the proprietor of Murton Chemical Works, in Dalton-le-Dale, Seaham Harbour, has lately been engaged series of experiments as to the oil producing of ordinary coal. Not content with the knowledge that he thus obtained, he went a step or two beyond and assured himself that the immense quantities of what is commonly called "shale" in another word the "waste" from the coal pits can be made by a certain process to produce a large quantity of oil and grease, of excellent quality. We have been advanced as a maxim in moral philosophy there is some good in things evil, would men out." The remark seems to be in some applicable to matters relating to physical Mr. Jossa intends to take this shale— far been regarded worthless—this veritable rubbish, this refuse, which has laid for years in large heaps about pit backs—a piece of which any one might and examine, and throw down again as hard, dry, and devoid of any virtue and pass it through an ordeal which shall reduce it to an oleaginous state.

There can be no doubt that the counties of Durham and Northumberland offer a fine field for enterprise of this nature, owing to the vastness of their coal beds, and the immense stock of debris that is constantly been created by the separation of good from bad coal the yield of' the various colliers. In mines in this quarter there is a layer of shale of 2ft 6in., and large quantities broken up in the workings, which are not deemed worth carriage to the top of the shaft. However, not only will there be plenty of raw material to keep the new works going, but there will, we feel persuaded, be a demand beyond the expectation of the promoter and undertaker of the scheme, on account of the North of England being the great emporium of trades requiring such commodities. From twenty-three to thirty gallons of paraffin could be had from one ton of shale. The paraffin already made is non-explosive, clear and gives a brilliant light. The system adopted for manufacture is easy and certain, and the results convince us that to Mr. Jossa we must look as the inaugurator of a new, and what hope will flourishing trade our midst.

Yorkshire Gazette, 3rd February 1866

.......

Description of the Works of the Earl of Durham

Within the last few years a manufacture of considerable importance has sprung up In Great Britain, of which very little is known save those closely interested in its success, or engaged in carrying it on. It pretty generally understood that treating any bituminous coal in the proper way, certain highly valuable products can obtained in lieu of gas. These may be classed under three heads, volatile combustible fluids, heavy oil, and the peculiar substance known paraffin, now largely employed In the manufacture of candles. It was long held, however, that these products could only extracted with profit from highly bituminous shale, such the somewhat celebrated Torbane Hill mineral, and few attempts were made in this country to obtain them from ordinary coal.

It is possible that so little was know about the coal oils that no appreciable demand for them existed, but the introduction petroleum and mineral lubricating oils from America quickly established market which became worth while supply, and such improvements have been introduced from lime to time in the distilling and purifying apparatus that, have said, the conversion of bituminous coal, as well as shale, into oil has become a branch of manufacturing industry, gaining in importance and extent each day.

The discovery of the fact that oil could obtained destructive distillation appears have been first made Clayton 1739. In the year 1805 Mr Northern called attention coal gas, and as a matter of course, in making it obtained considerable quantity of crude oil, little importance was attached to the circumstance, and the matter was not pursued until the middle of the present century. The only result, indeed, which appears have followed from Northern's labours as far concerns coal oil events, was the manufacture of tar in considerable quantities for the use our navy replace Archangel tar. which had become scarce and dear. Young took out his celebrated patent, and from the moment he undertook the manufacture of coal oil commercial scale it may be regarded as having been established a permanent basis this country. At a comparatively early stage Young obtained from 100 parts of canel coal, 40 of oil an 10 paraffin, while the residual coke was by no means valueless. It was sufficient to prove that the process could made remunerative, and very considerable sums are now embarked in the business in various places in Great Britain.

Lord Durham is about to establish works for the manufacture of coal oil at Fence Houses, which, when completed, will cover several acres, and will possibly constitute the most extensive establishment of the kind in the kingdom. The apparatus present consists of twenty retorts, constructed two different systems with view to determining which is the better the two. The stills for the purification of the crude oil have not yet been erected. (reprinted from The Engineer).

Durham County Advertiser, 13th July 1866

.......

Patents

1261. To Ferdinand Jossa, of Phoenix Oil Works, Fence Houses, in the county of Durham, Manufacturing Chemist, for the invention of "improvements in lubricators for the supply of mineral .and other oils to bearings and journals of shafts, pit tubs, and other parts requiring lubrication." 24th May 1867

London Gazette, 24th May 1867

.......

Bankruptcy Court

Re Ferdinand Jossa, Sunderland, oil merchant.

The meeting was for last examination and discharge. Mr Hodge for the assignees; Mr Brignal for the bankrupt.

The Bankrupt, examined by Mr Joel, said: I commenced business at Murton Colliery as chemical manufacturer in 1860. I had no partner. I had £1,000, which I brought from the Continent. I continued the manufactory up to the middle of 1865. I gave up that business because I lost so much money by it. I disposed of it to Thomas Vaughan, of Middlesborough. I owed him £1,000 for advances, and he discharged me from payment. I owed about £300 besides the sum due to Vaughan, who agreed to pay these debts. There was no valuation of the works before I sold them. There were no debts in respect of the factory. There were books; they were kept by the foreman, and were left there. After disposing of the factory, I built one of my own at Fence Houses, for the purpose of making shale oil out of it. I spent nine months in experiments; they were very expensive, and I lost thousands of pounds. Mr Morton advanced me £300; I returned it in merchandise. As soon as the oil was well up, the price suddenly fell from 6s. To 1s. 3d. per gallon. After ceasing to make shale oil, I had good credit, and thought I would recover myself. I cannot tell what I was owing then; perhaps £3,000 but all the documents are preserved, and are in court. I made, perhaps, 5,000 gallons; it was used in making grease, and I built factory for the purpose. I ceased in 1867. I had not money to pay my debts. I had furniture which realised £164. (Having been examined to particulars in his accounts, he continued.)

My accounts show that in October received £1,645, paid £1,213; and that in November I received £1,649, and paid £448. Within eight days of my bankruptcy I received £210, and paid £60. I don't know how much money I had in my possession at the time of bankruptcy. Mr Joel said the examination would have to go on for a very considerable period, and he thought he had got from the bankrupt sufficient to justify an adjournment, in order that the bankrupt might have opportunity of rectifying the accounts.

His Honour said there was a great deal to explain, arising out of the accountant's report to him. In one part £633 was accounted for.

Mr Brignal thought the bankrupt would be capable of explaining it. His Honour adjourned the meeting to the 5th of April, and said if the bankrupt had a statement to make in the meantime he had better file it. Mr Brignal said he would be able to cut down the balance to a considerable extent; and he thought it arose from some confusion in the renewals of the bills.

Newcastle Journal, 24th March 1869